June 27, 2022

Facts

Fabryki Mebli “Forte” SA was the owner of the following Registered Community Design in relation to “furniture”, registered on 17 September 2013 (the RCD):

In March 2016, Bog-Fran sp zoo sp k applied for a declaration of invalidity of the RCD on the grounds that the RCD was not new and that it lacked individual character under Article 4, read in conjunction with Articles 5 and 6 of the Community Designs Regulations (6/2002/EC). In support of its application, Bog-Fran submitted the following evidence:

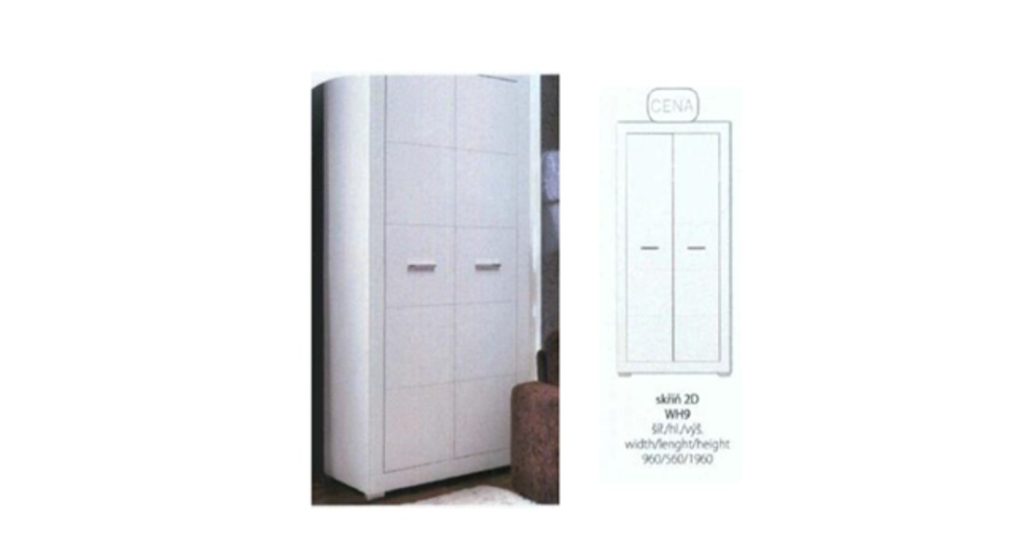

- an extract from a catalogue entitled “NABYTKU – Novinka 2008 – WHITE” containing the following representations of a wardrobe called “skrin 2D WH9” to which the earlier design had been applied:

2. an invoice, in Czech, dated 14 August 2008 relating to the printing of 25,000 copies of the catalogue; and

3. three invoices, dated 14 August, 4 November and 28 November 2008 respectively, relating to sales of furniture to A JE TO CZ, s.r.o., with confirmation of the receipt of the goods referred to.

The Invalidity Division of EUIPO upheld Bog-Fran’s application, finding that the RCD did not have individual character under Article 6 of the 2002 Regulation and was therefore invalid. Fabryki Mebli appealed, and the Third Board of Appeal upheld the appeal, annulling the Invalidity Division’s decision on the ground that the earlier design had not been made available to the public in accordance with Article 7(1) of the 2002 Regulation (and so could not be raised against the RCD).

Bog-Fran appealed to the General Court, which found (in an unpublished judgment Case T-159/19) that the BoA had wrongly found that Bog-Fran had not established disclosure of the earlier design in accordance with Article 7(1). The GC said that the evidence adduced did indeed constitute disclosure and that it was for the BoA, in view of that evidence, to presume disclosure before considering, if applicable, Fabryki Mebli’s arguments alleging lack of knowledge in the circles specialised in the sector concerned of the events constituting disclosure. The case was remitted to the BoA.

This time the BoA dismissed Fabryki Mebli’s appeal against the original Invalidity Division’s decision, finding that Fabryki Mebli had not established that disclosure could not reasonably have become known to the circles specialised in the sector, and concluding that the earlier design had been made available to the public (and so could be raised against the RCD). The BoA found that the RCD did not have individual character. The designs were for wardrobes, the designer’s freedom was not limited and the informed user would, as a result of his or her interest in furniture, have a relatively high degree of attention. After considering the similarities and differences between the designs, the BoA found that there were only minor differences between them which were not sufficient to produce a different overall impression on the informed user.

Fabryki Mebli appealed to the GC, alleging that the BoA had been wrong to find that the earlier design had been disclosed in accordance with Article 7(1), had incorrectly divided the burden of proving knowledge of that disclosure by the specialist circles in the sector concerned, and had been wrong to find that the RCD lacked individual character.

Decision

Disclosure of earlier design

Fabryki Mebli disputed the veracity and reliability of the evidence of disclosure produced by Bog-Fran.

In response, Bog-Fran submitted that Fabryki Mebli’s argument was inadmissible as the GC had already ruled on the probative value of the disclosure evidence, meaning that the matter was res judicata.

The GC agreed with Bog-Fran. The GC had indeed already ruled on the authenticity of the evidence and had found that the documents relied on established the veracity of the disclosure events. Accordingly, it had said that the BoA should have presumed disclosure of the earlier design before considering arguments on whether the disclosure was known to the circles specialised in the sector. These findings had formed the basis of the GC’s decision that the BoA had infringed Article 7(1). Accordingly, the findings were indeed covered by res judicata.

Fabryki Mebli also argued that the BoA had wrongly attributed the burden of proof of disclosure and that therefore it had not been entitled to rule on whether the circles specialised in the sector had come to know of the disclosure.

The GC noted that, according to case law, a design is deemed to have been made available once the party asserting it has proved the events constituting disclosure. To rebut that presumption, the party challenging disclosure must establish that the circumstances of the case could reasonably prevent those facts from becoming known in the normal course of business to the circles specialised in the sector. The analysis therefore involves a two-stage test. The GC held that in the light of the proven existence of events constituting disclosure of the earlier design, the BoA had rightly found that it was for Fabryki Mebli to establish the second part of the test.

The GC noted that the BoA had found that Fabryki Mebli had failed to adduce any factual evidence or argument that did not amount to mere insinuation to show that disclosure could not have become known to the circles specialised in the sector. Fabryki Mebli’s allegations were not substantiated.

Individual character

Fabryki Mebli argued that the photograph of the earlier design was incomplete, as it excluded the top part, meaning that the design could not be discerned sufficiently.

The GC noted that case law has established that part of the product represented by a design that is outside the user’s immediate field of vision does not have a major impact on that user’s perception of the design, and the overall impression produced by a design must be determined in the light of the way the product is used, in particular on the basis of its handling by the user.

It was common ground that wardrobes are intended to be placed on the ground, against a wall, and that they are most often handled by opening their doors. Therefore, the GC said, their rear, lower and upper surfaces will be, at the very least, not very visible, and unlikely to influence the overall impression on the informed user.

Consequently, the GC said that the BoA had been right to compare the designs on the basis of the images produced by Bog-Fran.

As for Fabryki Mebli’s argument that, because of the differences between the designs, the BoA had been wrong to find there was no different overall impression, the GC noted that, according to case law, differences will be considered insignificant where they are not sufficiently pronounced to distinguish the goods or offset the similarities in the perception of the user. Further, the greater the designer’s freedom in developing a design, the less likely it will be that minor differences will be sufficient to produce a different overall impression.

The GC held that the difference in colour between its design and the images of the earlier design (white as opposed to “greyish”) was so slight as not to be able to influence in a decisive manner the overall impression produced by that design.

Accordingly, the BoA had not erred in assessing that the RCD lacked individual character.

The appeal was dismissed, meaning that the Invalidity Division’s original decision that the RCD was invalid applied. (Case T-1/21 Fabryki Mebli “Forte” SA v EUIPO EU:T:2022:108 (2 March 2022) — to read the judgment in full, click here).

Expertise