July 8, 2022

The Gambling Commission (“Commission”) has recently published the new guidance (“Guidance”) that it expects remote gambling operators to follow to discharge what will become their strengthened obligations to identify and act to protect customers at risk of harm when new rules (SR Code 3.4.3 of the LCCP) come into force on 12 September 2022. The Commission has not updated the non-remote version of its Customer Interaction Guidance and has not given any indication that it will.

The Guidance provides further information to operators on:

- identifying vulnerable customers;

- the indicators of harm operators must monitor for;

- using automated systems to “act” (not just interact) to address harm in real time or near real time; and

- how to evaluate the impact of customer interactions.

The guidance breaks down new SR Code 3.4.3 into each of its requirements (“Requirements”). It explains what the ‘Aim’ of each Requirement is and then provides ‘Formal’ and ‘Additional’ guidance that operators will be expected to take into account. Operators must be able to demonstrate to the Commission how the Guidance has been implemented into their overall customer interaction systems and processes.

The Commission published the Guidance in June to give “the industry time to prepare for the changes,” but achieving “full compliance by September” (to meet the Commission’s expectations) is likely to be very challenging, particularly where system changes (notably where there is reliance on third parties) need to be made, so operators should be acting now.

In many respects the updates to the Guidance reflect the Commission’s existing expectations (whether or not grounded in regulation) as amplified in compliance assessments and/or licence reviews over the last few years. As such, on a first read, one is left to consider how much of a sea-change the Guidance actually is. On closer inspection, the Guidance does introduce new requirements but much of the impact on operators will flow from the organisational/governance implications that many will see as considerable when compared to current practice.

In this article we examine those areas of the Guidance that we consider to be new, noteworthy or (to us at least) unclear. However, operators should be reviewing the Guidance in full to identify where their safer gambling processes need to be reconfigured to be in a position to demonstrate how the new standards are being met from 12 September 2022. Experience from previous regulatory changes (such as the changes on High Value Customers) and subsequent Commission compliance assessments indicates that it would be prudent to do so on paper in checklist format and to ensure there is senior level (PML) oversight and accountability for ensuring any necessary changes are made and implemented effectively.

1. Assessing the New Requirements

The Guidance is split into four sections:

- Section A: General Requirements

- Section B: Identify

- Section C: Act

- Section D: Evaluate

Section A: General Requirements

Requirement 1

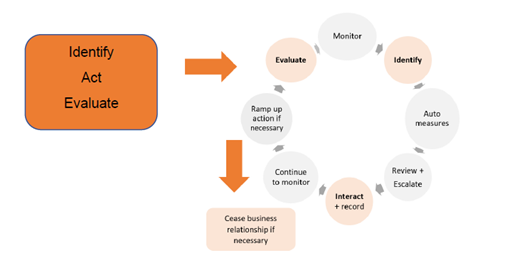

Under Requirement 1, operators must implement effective customer interaction systems that embed the three elements of customer interaction: namely, to identify, act and evaluate. This is a cyclical process, as diagrammatically illustrated in the Guidance as follows:

Operators must monitor for “unusual and risky” patterns of behaviour from the point of account opening. Processes should be capable of: (i) risk weighting different markers to identify when customers may be suffering harm associated with their gambling; (ii) acting in a way that is proportionate to the harm presented (both in terms of the type of harm and its severity); and (iii) evaluating whether the steps taken were effective, both at a macro and micro level (see Requirements 11 and 12 in particular).

The Commission’s shift towards “action” (rather than “interaction”) is particularly notable, and mirrors its increasing expectation that operators should act on behalf of customers and be proactive in limiting or blocking customers who exhibit stronger markers of potential harm, rather than sending generic and tailored safer gambling messages (albeit “interaction” and “action” are used throughout the Guidance in a manner which doesn’t lend itself to certainty of expectations). As such, the Commission is clearly advocating a much more interventionist approach to player protection, which demonstrates a significantly different approach to the more “customer-led” approach the industry has hitherto been operating.

Section B: Identify

Requirement 3: Vulnerability

Requirement 3 states that “Licensees must consider the factors that might make a customer more vulnerable to experiencing gambling harms and implement systems and processes to take appropriate and timely action where indicators of vulnerability are identified. Licensees must take account of the Commission’s approach to vulnerability as set out in the Commission’s Guidance.”

On its face, Requirement 3 goes to the heart of one of the key licensing objectives of the 2005 Act, which is to “protect vulnerable persons from being harmed or exploited by gambling.” Where vulnerabilities are identified, operators will be required to navigate the tricky balance between consumer freedom and ensuring such persons are protected from harm (this need for balance is at the heart of DCMS’s review of the 2005 Act). When operators get that balance wrong vulnerable persons can be exposed to both significant harm on the one hand or inadvertent discrimination on the other.

The Guidance attempts to provide a ‘catch-all’ definition of a vulnerable person as “somebody who, due to their personal circumstances, is especially susceptible to harm, particularly when a firm is not acting with appropriate levels of care”, and gives various examples of the types of situations which may make someone vulnerable, including those which relate to “health, capability, resilience, or the impact of a life event such as a bereavement or loss of income.” Vulnerability is difficult to define precisely, as it can depend heavily on circumstances, and there are many different types of personal vulnerabilities that may (or may not) pre-dispose a person to suffering harm associated with gambling. Operators will need to think carefully about those vulnerabilities which increase or decrease the risk that a customer experiences negative outcomes from gambling when designing their customer interaction frameworks to ensure they respond quickly when vulnerability is identified.

Of course, a customer’s personal circumstances will not often be known to a remote operator (which is acknowledged by the Commission), particularly as a result of the fact a customer is not actually present for the transaction (unlike in retail gambling environments). Formal guidance 3D explains that operators will be expected to “understand whether a customer is at greater risk of experiencing harm and to what extent” and to “take timely action in response to the information they have.” That does not go as far as saying that operators must carry out proactive vulnerability screening by collecting information about their customers’ personal circumstances. But operators will need to design their safer gambling frameworks so that when information is available to them that may indicate that a customer is more vulnerable to harm, they have systems in place to assess that information and react accordingly. Importantly, operators will need to use information collected for an entirely different purpose (e.g. a bank statement collected for AML/CTF purposes) and identify when information contained within those documents indicates that a customer may be vulnerable. For that reason, operators will need to consider whether staff in and outside their safer gambling teams require additional training to identify markers of potential vulnerability. The requirement to use information that an operator has obtained in order to manage one particular risk for the purpose to managing other risks is not new. But we expect the regulator to focus on this requirement in compliance assessments and operators must be prepared to demonstrate how they meet it.

Formal guidance 3F provides examples of the “factors” that might make an individual more vulnerable to experiencing gambling-related harm, though it is unclear how and when an online operator should determine that a customer “has a higher than standard level of trust or high appetite for risk” or “takes a high-risk strategy, particularly if inexperienced”. Clearly, certain gambling products afford a significant upside on a small stake, with very low chances of success (e.g. lotteries, multi-leg accumulators). Surely the Commission doesn’t mean to suggest an individual who wagers on products with very long odds, but potentially high returns, is vulnerable as a result?

The Guidance also invites operators to treat an individual “engaged in an activity which is highly complex” as a marker of vulnerability, and gives the choice of “highly complex betting products” by “new” or customers who “have little knowledge” as an example of when a customer may be exhibiting vulnerability to suffering harm, though gives no evidence to support these conclusions, nor clarity about what they actually mean. This is certainly one area where the Guidance is less helpful than it needs to be.

The “evidence of harm” the Commission cites in its ‘Additional guidance’ to Requirement 3 is to repeat misleading statistics which have previously been challenged in response to the Commission’s consultation on affordability. The Commission cited a survey conducted by the Money and Mental Health Policy Institute “that found that one in four (24%) of respondents…of people with lived experience of mental health problems experienced financial problems as a result of gambling online”. This was called out by the industry as a misrepresentation of the survey results and related solely to the subset of those survey respondents who had gambled online rather than to all survey participants. The survey findings were also based upon a small sample of respondents (n=134), indicating that around 30 respondents claimed to have experienced financial problems. Once again, it was exceptionally misleading for the Commission to present this as evidence in support of the contention that unaffordable gambling is a ‘large-scale issue’ and its repetition in this Guidance is disappointing and cannot go unnoticed.

The introduction of requirements to identify and act on signs of vulnerability (particularly when that concept is still poorly understood and difficult to define) may sow the seeds of further player litigation, creating opportunities for those with both genuine and fictitious vulnerabilities to claim that they should have been prevented from losing. Operators can help to manage this risk by building systems capable of reacting promptly when markers of vulnerability are presented; but no system will stop all vulnerable customers from suffering harm.

Proponents of consumer redress in these circumstances often promote financial compensation based on losses, though this brings with it risks of perpetuating harmful behaviour by those vulnerable customers who do genuinely suffer harm through gambling, and can also create counterintuitive incentives for customers to gamble ‘risk free’ in the hope of seeking to recover losses in an action alleging the operator failed to identify that they were vulnerable.

Requirements 4 and 5

Requirement 4 requires operators to put in place “effective systems and processes to monitor customer activity to identify harm or potential harm associated with gambling, from the point when an account is opened” with the objective that “indicators of harm are not overlooked while the operator waits for a pattern of behaviour to emerge.” The Guidance sets out at Requirement 5 the range of indicators which must (as a minimum) be included as part of an operator’s list of indicators to identify harm or potential harm associated with gambling (we discuss these in further detail below):

- customer spend;

- patterns of spend;

- time spent gambling;

- gambling behaviour indicators;

- customer-led contact;

- use of gambling management tools; and

- account indicators.

Operators are expected to balance all the markers of potential harm exhibited by customers to then act in a way that is proportionate to the perceived harm. The Commission is clear that it will expect operators to use “a mix of automated and manual processes” to monitor harmful behaviours in real time (or near real time), as well as draw on information collected through customer contact and previous customer interactions, to make “better and quicker decisions.” To do so, operators may need to redesign their player account management systems to ensure that relevant staff have access to “a more complete picture of the customer’s activity”.

The Commission’s position on affordability (paragraph 4F and 5C) is largely unchanged, though the Commission notes that its guidance on “financial risks of binge gambling; clearly unaffordable gambling over time and financial vulnerability” will be updated following further consultation expected later this year.

The Commission expects that industry consolidation will continue and explains (at paragraph 5C) its expectation that operators should ensure that customer interaction processes keep pace with any increase in demand that results from M&A activity in what we assume to be a nod to the challenges that can often result from linking player activity that occurs across different platforms and brands within a combined group with huge operational challenges involved in achieving technological integration.

One particularly notable aspect of this part of the Guidance is to “identify harm or potential harm associated with gambling, from the point when an account is opened”. To date, most operators’ safer gambling algorithms are largely based on change, in that they look for spikes in behaviour and/or focus on how a customer’s use of the service evolves. Clearly, the new expectation is that operators need to identify potential vulnerability from the get-go, which may impose far more of a burden than it first suggests.

Requirement 6

Requirement 6 requires operators to ensure that, where they contract with third party B2B providers, they remain responsible for ensuring that systems and processes are in place to monitor a customer’s total activity to ensure that the minimum indicators of harm are identified. The Commission appears to be concerned by the number of instances in which its licensees have had arrangements with one or multiple B2B providers which renders the operator technically unable to monitor customer activity at an account level, though this is not made entirely clear.

Similar challenges were faced by operators when the Commission introduced its “reality check” requirement in 2016 (RTS 13B), which led to the Commission granting operators and suppliers an extended grace period in which to technically deliver a solution, as well as flexibility within the 13B Implementation Guidance to deliver solutions via “Player account level”, “Product level” or a “Hybrid” solution. This flexibility took account of the fact that the technical infrastructure used by operators (and their B2B suppliers) to deliver gambling services to British consumers varies considerably, and acknowledges that there can be very significant challenges to delivering solutions capable of tracking gambling transactions which technically occur on multiple platforms.

However, the Commission is clear in Requirement 6 that it expects operators to use systems which “always have oversight of customers gambling activity” which are capable of monitoring all markers of potential harm, even where use of software from third party B2B suppliers renders that technically more difficult. Given the challenges this may present, operators should be thinking now whether their systems are capable of meeting this expectation and making any necessary adjustments sooner rather than later.

Requirement 7 and 11

Requirement 7 states that an operator’s customer interaction processes must flag indicators of harm “in a timely manner for manual intervention and to feed into automated processes as required by paragraph 11.”

Operators must now implement automation within their customer interaction processes to respond to stronger markers of harm if their manual processes are not capable of taking swift action (as will be the case for almost all operators). Where a “significant level of harm is identified” the Commission explains that “it will often be appropriate to place a block on further gambling until an action has taken place.” Operators will need to design their customer interaction processes to make clear what types or level of harm will lead to a block or restriction. Moreover, operators should be able to articulate why, in certain scenarios, a block is not required and why a customer may be able to continue playing whilst further assessment/monitoring occurs.

Formal guidance 7B goes on to state that, where automated processes are applied (such as a block or restriction), an operator “must manually review their operation in each individual customer’s case and the licensee must allow the customer the opportunity to contest any automated decision which affects them.” While creating an expectation to use automation to respond to harmful behaviours in real time is difficult to argue against, imposing a requirement to “manually review” all automated decisions risks (if read literally) creates a very significant resourcing demand on the industry (by undermining the benefits of automation), with no apparent justification other than to be “consistent with data protection requirements”. We see no reason why the Commission would bake into its regulation a requirement to comply with data protection laws (which operators are already bound by). Please see our blog piece for a separate article examining this Requirement in further detail.

Section C: Act

Requirement 8 and 9

Operators must tailor the action they take in a way that is proportionate to the potential harm identified. This may mean taking strong or stronger action straight away, rather than increasing action gradually, including by refusing service where necessary.

While making clear that operators must implement automated processes capable of applying limits and restrictions when “strong indicators of harm” are present, the Commission does not define what strong indicators of harm are. That assessment must now take account of a “specific range of indicators” (none of which are new) but must be “defined within the licensee’s processes”, leaving discretion to operators to determine when the risks presented by players means they should be stopped from gambling further.

The Guidance has been described by the Commission as a “far more prescriptive” approach to regulating customer interaction and as a move away from the Commission’s favoured outcomes-based approach to regulation. However, its failure to define when limits should be applied (and with many examples representing “edge cases” only) means there will be significant variations between how sensitive operators’ processes are to risk and how much protection is actually afforded to British players.

It would be easy to criticise the Commission for this as a “missed opportunity”, but, in truth, there is currently no practical way of prescribing what “strong indicators of harm” means, given how poorly gambling-related harm is understood and how difficult it is to distinguish between behaviour that is harmful for one, and perfectly normally for another. Any acknowledgment of this challenge will not stop Commission officials imposing their view of what strong harm looks like (and when customers should have been blocked), which we continue to see in compliance and enforcement cases defined (in effect) by reference to gambling more than “average monthly income”, despite the question of affordability (and its role in reducing gambling-related harm) being deferred to a later consultation.

Requirement 10

Operators will be required to prevent marketing and new bonus offers where strong indicators of harm are present. Aside from the challenge of defining what “strong indicators of harm” actually are (as discussed above), it is worth noting that paragraph 10D of the formal guidance under Requirement 10 sits at odds with most operators’ terms and conditions.

Please see blog piece regarding consumer protection considerations (available here) for commentary on the Guidance from a consumer protection perspective.

Section D: Evaluate

Requirements 12 and 13

While in many ways the new Guidance requirements to ‘evaluate’ the impact of customer interactions are reinforcements of what is already in the existence guidance, the Commission has made its expectations of operators much more explicit.

Operators are expected to implement processes which assess the impact of each interaction or action taken, including by reference to a customer’s behaviour and any continued risk of harm. In order to do so, operators will need to define an objective or intended outcome of each action and design processes which monitor whether or not the objective was achieved. Operators will need to use these processes to determine whether or not further action is needed.

The challenge of implementing an evaluation protocol capable of assessing the impact of actions on a customer-by-customer basis should not be underestimated. While it is not a ‘new’ requirement, the Commission has moved to being much more prescriptive in its expectations, and we expect there will be many operators who are still some way off being able to deliver a solution capable of truly evaluating the impact of each interaction in anywhere near the level of granularity that the Commission’s Guidance seems to require. Operators will need to think carefully about how their systems will need to be redesigned to meet these expectations, including whether there are alternative ways of achieving the same or similar regulatory outcomes (e.g. by segmenting customers who exhibit the same markers of harm and defining expected outcomes in customer behaviour / continued risk of harm when the same action is taken).

Requirement 14

Requirement 14 is new and requires operators “to take account of problem gambling rates for the relevant activity published by the Commission in order to check whether the number of customer interactions is, at a minimum, in line with this level.”

Requirement 14 somewhat cuts across the logic of the remainder of the Commission’s other updates, which requires operators to tailor their actions based on the severity of the harms identified, rather than mandating a minimum number of interactions. The intention of the new Requirement is presumably to require operators to have regard to the latest problem gambling rates when designing how their safer gambling systems should react to markers of potential harm, though the logic of tying this to “the number of customer interactions” seems poorly thought through.

2. PART 4: CONCLUDING REMARKS

The Commission explains that the Guidance will be kept under review and updated over time, for example, “where new evidence or risks emerge” or to “reflect lessons learned from compliance and enforcement activity.” This makes sense, though does beg the question whether and when future updates to the Guidance will be the subject of further consultation (as we believe they should be). This will happen when the Commission consults (again) on the issues of ‘affordability’ and ‘financial vulnerability’ (which may well take account of a framework established by the Government’s imminent White Paper) whereas future updates to the Guidance may not be.

The need for consultation becomes critical where, as we have seen, the Commission uses its guidance as a means of effectively imposing new requirements on operators. While guidance is helpful to explain how operators must meet their obligations under the LCCP, it is not an alternative to substantive regulation made according to the consultation process prescribed in the Gambling Act 2005. If the Commission wishes to increase regulatory requirements, the additional regulatory burden must (as a minimum) be the subject of meaningful consultation prior to implementation.

Operators will have a big task ahead of them for the next three months in implementing those necessary updates to their customer interaction systems and processes to ensure compliance with the Guidance. Unfortunately, although the Guidance is almost double the length of the previous version and is more prescriptive with its Requirements in many areas, in others it still lacks the clarity that many in the industry would have hoped for and which the Commission had the opportunity to provide. How the Commission will enforce the Guidance from 12 September remains to be seen but, for now, operators should undertake a holistic review of their customer interaction systems and processes, plug any gaps and record how they are complying (or at least believe they are complying) before the deadline.

The new Customer Interaction Guidance can be accessed here.

Expertise

Topics